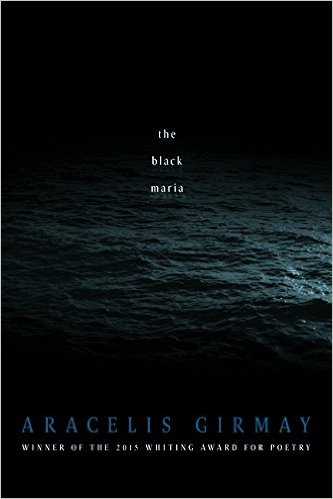

The country is in unrest, is what they say. And it is. For many it is dangerous. At times, it is numbing and at times it makes little to no sense why we are divided over the issues we are, especially that black lives matter. I attended the Women’s March on Washington and I remember my friends, braver than I, in what felt like a cramped house built of white activists trying to start a chant, just a simple, black lives matter. The chant lasted a short time, exhilarating in the moment, but fell flat in the sea of paper mache uteruses and felt pussy hats, I do admit I wore one ignorantly. But I, and many others, felt that a march designed by its committee to rally for equality despite the administration in the White House had ultimately failed in its practice to highlight trans issues and the phrase that has somehow become controversial, “black lives matter.” Though I do not think her book was directly in response to the Black Lives Matter movement, I do think Arecelis Girmay’s The Black Maria is an artful voice that is important to our political context, even here in Rochester. Girmay artfully guides her reader through the grief, the joy, the specificity, the expansiveness, and the misunderstandings of blackness, a journey which at times is soft and intimate as orange fibers but which also pounds deep in the marrow of bones.

The lightly experimental book, the black maria is divided into two sections, “elegy” and “the black maria.” The “elegy” section follows, as is explained in the first poem “elegy,” four women named Luam who are in different locations and speak to the specificity of being human, of being outsider, and of course of being black in their specific timelines and locations. Girmay acts as tour guide, slowly unraveling their stories while also prefacing them with explanations for certain images and context.

Alongside toggling between narratives, we also begin to understand how the oceans and seas are important as bodies which contain countless unidentified black bodies. Of the water, she writes in her poem “black, full of language,” “about what I know about/ the beckoning of all that blue muscle, a kind of beast pawing at the bluff(s), /it is always carrying some otherelse/ almost here.” Much like the title suggests her poetics here are full; the reader is forced to ease up in the midst of her driving language with the repetition of “b” words and dwell on the animalistic nature of the water as it carries the otherelse, those who are not mentioned or implied, those who are other. Unfortunately, they do not make it here.

Girmay titles her book and second section from the misidentification of moon craters about which she writes that astronomers thought they were seas and named the basins “black maria.” This misidentification becomes extremely important to the second section especially, moving from anonymity of the sea as a mass grave to racial profiling, a “misseeing” in its modern contexts in her collection of “estrangements.” Of the names people commonly know as black victims of violent racial profiling, like Renisha McBride, Trayvon Matin, and Rekia Boyd, she writes a comparison to the misidentification of craters, “Naming, however kind, is always an act of estrangement. (To put/ into language that which can’t be/ put.) & someone who does not love you cannot name you right, & even “moon” can’t carry the moon.” Here she asks her reader to understand that though we can remember these names and advocate for justice, they are still missing from their families because of racial profiling and we can only be strangers to the personal nature of naming.

Though the book grieves the lives of many black people, Girmay also celebrates the art and advocacy of black communities, often referencing or writing to them. In “Moon for Aisha” she writes to poet Kamilah Aisha Moon, “I am thankful/for some inexplicable thing, /let’s call it ‘freedom,’ or ‘night.’” With this, as with many other instances in the book, she humbly notes that she does not work alone. She is influenced and inspired by poets working around her as well as artists who wrote in the past. In her acknowledgments, she explains, “It is my hope that while these poems mourn the dead and the bleak circumstances of our present, violent day, they are also a tribute to black joy, black art, black making, black life.” I, for one, would argue that she accomplishes this. Girmay captures the contradictions within blackness and asks the reader to understand that there is no simple dichotomy, only a body full of specific stories, many that will remain uncovered. The black maria implores us in this time of unrest, to listen and absorb.

Reviewed by: Gabriella Garcia