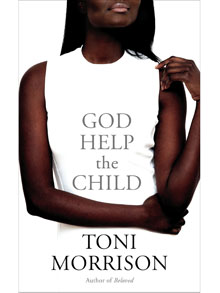

Crafting a unique, inspiring, and non-clichéd tale about a character’s “loss of innocence” is a daunting task. But in her 11th published novel, God Help the Child, Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison manages to pull it off nearly flawlessly.

23-year-old Bride has skin as black as midnight. Everyone she encounters envies her rare, exquisite beauty—though this has not always been the case. From the moment Bride was born, her light-skinned mother Sweetness knew something was wrong (“She was so black she scared me.”) Ashamed of her daughter’s unusually dark complexion, Sweetness considered Bride to be a heavy burden she was doomed to bear for the rest of her life. Consequently, unlike her friends, whose mothers showered them with an endless supply of love and affection, Bride grew up mistreated and neglected.

On several occasions, Sweetness admits to having treated her daughter poorly, though she justifies her selfish actions by claiming that young Bride did not understand the harshness of the world—that Bride’s black skin is “a cross she will always carry,” one which will either frighten white people or cause them to ridicule her. “I wasn’t a bad mother…” Sweetness asserts. “But I may have done some hurtful things to my only child because I had to protect her. Had to. All because of skin privileges.”

Years later, Bride has made quite the name for herself as a bright, confident, and successful corporate woman living in California. Her dark skin is no longer a source of embarrassment but rather one of admiration and adoration. The looks of disgust Bride had grown accustomed to as a child have now turned into ones of wonder and amazement, as Morrison writes, “The gasps her blackness provoked were invariably followed by the envy her beauty produced.” In fact, Bride has built up immunity so tough that she now considers herself a “deep dark beauty” instead of a “nigger girl.”

As the novel progresses, however, both mother and daughter come to understand “how childhood cuts fester and never scab over.” Despite being surrounded by luxury, Bride is still greatly affected by her loveless upbringing. As a direct result of having been deprived of physical contact as a young girl, adult Bride now delights in the mere satisfaction of being touched and craves the healing power of intimacy. This is only the beginning of a long and disturbing chain of events that eventually reveals the immense and everlasting repercussions of childhood trauma.

Reminiscent of Morrison’s earlier works, particularly Song of Solomon and Beloved, God Help the Child contains elements of magical realism that are characteristic of a mythic journey resulting in the achievement of selfhood. About midway through the story, Bride begins to notice unsettling changes in her physical appearance—including lack of body hair, unpierced earlobes, a flattened chest, and severe weight loss. Such shocking alterations seem to indicate a sort of regression: The gradual disappearance of the very characteristics that define Bride’s womanhood lead her to suspect she is self-destructing, reverting back to the “scared little black girl” she used to be.

What is even more bizarre, perhaps, is the fact that nobody besides Bride seems to acknowledge her striking transformation—and it is never explained. Unfortunately, Morrison’s attempt to integrate the technique of magical realism, most likely as a means of symbolizing the protagonist’s loss of identity, seems to fall short this time. Her inclusion of such elements is considerably underdeveloped, withholding too much information from the reader. Instead of flowing naturally with the rest of the story, it feels forced and unconvincing.

Morrison’s ability to create fragmented and multidimensional characters, all of whom are worthy of sympathy despite their significant faults, is commendable. At first, they seem to bear little to no resemblance to one another; as the story unravels, however, it becomes clear that there are several parallels drawing these characters hauntingly close together. Each has experienced profound hurt involving sexual abuse/molestation during his or her childhood years; this ultimately ties them all together by the novel’s stirring conclusion. Figuring out how to connect the dots is the most rewarding part for readers.

By attributing both positive and negative qualities to her characters, Morrison encourages the reader to think outside of strict binary oppositions—not in terms of black or white but rather in terms of shades of gray. In doing so, she forces the reader to withhold judgment, thereby establishing credibility for her beautifully flawed and realistic characters.

Overall, God Help the Child proves to be a powerful and compelling coming-of-age tale that touches on important topics like unbearable loneliness, profound regret, inconceivable heartbreak, and unconditional love. The beauty of Morrison’s lyrical prose perfectly balances the emotionally painful subject matter (Be warned: This book is NOT for the faint of heart), which makes for a quick yet satisfying read. Though it is apparent that some of Morrison’s ideas are not fully formed, creating a mild disruption at certain points in the narrative and leaving too many questions unanswered, the novel does ultimately succeed in accomplishing its central purpose of teaching the reader an important moral lesson: Every choice we make, whether consciously or unconsciously, can have devastating consequences on ourselves and others in the future. At the heart of the story, like so many of Morrison’s previous works, is the intense human yearning for love and belonging, a yearning which cuts so deep it defies even the greatest of life’s obstacles.

Reviewed by: Lindsey Moses