this day’s singular existence in time,

the native field flourishing selfishly, only for itself.

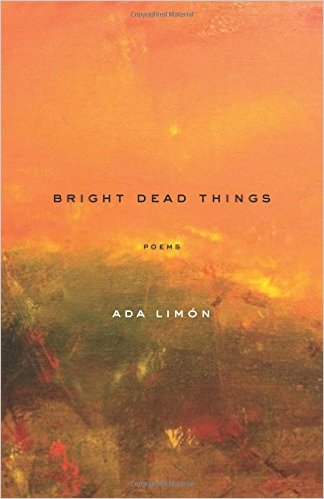

In Bright Dead Things, Ada Limón illuminates how one life is comprised of countless other lives that we exit and enter everyday. Limón creates an arrangement for readers, a selection that is not as frivolous as choosing a dress to wear, but rather which role to assume. Limón’s work is selfish, in that each poem is vastly self-centered and concerned with the condition of the speaker. Limón invites us into her imagination, into her long-held onto memories to share how she has grown and learned.

Though other figures are introduced, such as friends, brothers, parents, lovers, the speakers’ sole concern is of themselves. Bright Dead Things sifts through the mind’s vault, offering the familiar oddities and occurrences that follow us around. Limón reminds us how our past selves and future selves are just as much a piece of our current self. Along with Limón’s words, we travel from the dry heat of California, to horse farms in rural Kentucky, pausing briefly to find Brooklyn, only to forgo our future plans for a beer that will dull the senses.

Bright Dead Things assumes a rapid pace that appears to cover a large period of time. In one moment, we seize NYC as single women, feeling thrilled, ambitious and empty until we find ourselves suffocating in the open field that stands before our new farmhouse in the country.

Limón’s book has a pulse like that of a horse with an eight-pound heart. In her Pushcart Prize winning, opening poem, “How to Triumph like a Girl,” Limón writes about liking “the lady horses best”. “the huge beating machines / that thinks, no, it knows, / it’s going to come in first”. By beginning with a speaker who finds strength in femininity, Limón sets a tone of empowerment, specifically womanly strength that she will embrace and misplace along the way.

Early on, Limón’s established tour de force is tested in “Down Here” and “The Quiet Machine,” wherein the speaker begins to discover different kinds of crippling silence, or hushed shouting that was once expressed publically in the street. It appears that feelings, like sadness or anger, are not black-and-white, nor simple to detect.

Limón ages over the course of the book, discovering the covert pains of maturity and adult relationships. Halfway through, we are introduced to a mother figure, whose death is a confusing, damaging experience for the speaker. In “In a Mexican Restaurant I Recall How Much You Upset Me,” Limón employs a litany of “you” statements to extol the mother:

you the flag in the moon, and the moon,

you the garden and the grave,

you who I held as the last air left.

And then you were what? What then?

Limón continues to call this mother, this “you,” “mean,” highlighting several instances to complicate the child-mother relationship. “The Riveter” recounts the process of dying, in which the speaker is taking notes as callously as if she is dealing with a client. This section epitomizes the self-focused writing of Limón. The speaker prepares for the mother’s death, lamenting that the aftermath will destroy those who remain:

her work, was to let the machine

of survival break down,

make the factory fail,

to know that this war was winless

to know that she would single handedly

destroy us all.

The Mother figure is the only occasion when the narrative briefly removes its spotlight from the speaker. Once the mother is gone, Limón reverts to a file of romantic relationships, withholding specifics to emphasize the speaker’s experience. These relationships indicate growth within the speaker, and how the speaker gives love to receive love, and ultimately emerges from the relationship more in love with herself.

Limón ends with the myth of Icarus in mind. Like Icarus, the speaker endeavors to fly whilst being dragged down by reality. Never once does the focus depart from the speaker, rendering Bright Dead Things a refreshing read that reminds us of the duty we have to ourselves. By covering a lifetime and an entire American landscape, Limón declares that we do not exist only within the present minutes. Wherever we may venture, we carry fears, thoughts, and practices, whether they stem from a former time or a potential time. Even amidst the chaos, the identity crises, and the face of death, Limón relishes in the pleasure of existence.

I’d want to fall from the terrifying height

of her, the dust of my years crazy and flashing

lit up by the victory of my disastrous flight.

Reviewed by: Allison Fox