In his debut poetry collection, King Me, Roger Reeves presents the world as fractured, nearly irredeemable, yet overflowing. With a precision and grace, Reeves reveals the hope and redemption in the smallest fragments of humanity—and in the act of poetry itself. King Me converses with many views of reality at once, setting out from the personal and expanding to incorporate the vast and pained landscape at the intersection of history, blackness, and American identity. Reeves’ poetry cannot be contained: images spill over lines and evolve upon their spilling, forests of animals and cities of speakers appear and reappear, accumulating context and meaning within the collection in each iteration. King Me has a firm foundation in the lyric, where scenes unfold from the intersection of humanity and nature. The collection is a whole of many discrete realized parts, at once lush, desolate, distant, using association over lines, stanzas, and pages, in order to disassociate and reclaim.

Reeves’ poetry reaches to gather what remains of our world, and bring it to light. In the first poem of the collection, “Pledge,” the speaker takes on the author’s name, and announces his mission to leave his unnamed city, and in doing so collects a tapestry of people and images that is exemplary of his aesthetic and his overflowing style:

“I leave the numbers by which I know this city,

its epistemologies and apartheids, its mornings,

its slips of paper, its silvers and its seeds,

its dry floors and short showers, its roosters

that cannot distinguish between the blue of morning

and the blur of night. I leave the coffee spilled

onto the floor of the bus, your hand between my legs—

I leave, I leave—this will surely leave a stain.”

In this poem the word “leave,” repeated in almost every stanza, functions as both a physical departure—a retreat from the world he knows—and a leaving in terms of letting things be. In retreating from place, the speaker is dislocated—alienated—able to oversee and exist in the vast landscape that will unfold throughout the book. In leaving things be—even the contradictions (earlier he mentions “the man with his one leg turned backward / to walk this street twice as pure contradiction”)—the speaker, Roger Reeves, announces an aesthetic intention based in realism as well—the small things of discord are left where they are and given attention. An effective opening poem invites a reader into the poet’s world—Reeves’ opening poem, in its brilliance, brings the poet to the reader’s world. In announcing his dislocation, and embracing the reality of the coffee on the floor of the bus—that which will surely leave a stain—Reeves situates his poetry in the ability to contain and explore many contradictory facets of reality at once.

Reeves’ explorations of reality tend toward the surreal, “the ‘superior reality’ of discomforting associations…” (Princeton, 1377). In effect, these delve deeper into the associations that on a daily basis would be left unexplored: in “Before Diagnosis,” the speaker’s sister, struggling with mental illness, “In the last moments of a sun, my sister / says a man is chasing a goose through the snow.” In this closing image of the poem, a sun—one unspecific and detached—sets, and the sister’s faltering grip on reality manifests in nature: a man chasing a goose. Moments like this permeate King Me, where Reeves not only constructs the pathetic fallacy, but also makes it reality. The sister’s loosening sense of the real becomes a manifestation in nature—not a dream or a comparison—but a vivid metonymic scene within the poem.

Reeves’ surreal imagery allows him to delve deep into the breaking points in the world, in which the fractures reveal the nature and emotion of reality. These fractures allow for synthesis and growth, images turning and growing, twisting toward a new and different understanding. Reeves’ treatment of the lynching of Emmett Till in “The Mare of Money,” from the point of view of a dead horse as witness, underscores his project of poetry as a place for collecting the fragments into a broken but graceful whole. This poem exists very much within the consciousness of black identity in America, another theme of Reeves’, where history is an every day burden, a wound for which, from the point of view of the dead horse, there is no easy cure:

“she does not get the luxury

of a lyric—a song that makes

our own undoing or killing sweet

even as we go down

into the fire to rise as smoke.”

In this poem, as in many others, Reeves reaches for redemption within the fracture—there is no easy lyric sweetness, but there is the cold grace of smoke rising from a fire. Reeves also engages with the idea of a poet’s role in society: the poet as witness of grace, the poet as singer, as revivalist, the poet as creator of the document that carries the true weight of reality, beyond the surface facts. The mare, looking eye to eye with the body of Emmett Till, attempts to witness the brutality of his death:

“as though decaying is something

that requires a witness

—as though the mare might say:

On Tuesday after the rain fell,

the boy’s neck finally snapped

from the weight of the mill fan;

he never looked at me again.”

This attempt to aestheticize and replay the violence of lynching is interrupted by the speaker on behalf of Emmett Till: “Or the boy might say: / No more.” This poem implies that the role of the poet is not solely to witness—not to rearrange the words of a trauma for aesthetics—but to witness tragedy with grace, not reveling in it. The speaker has Emmett speak “no more,” gesturing to an end to lyrical aestheticizations of violent death, toward a kind of redemption beyond the history of American racial violence.

Reeves’ debut collection is limitless, neither bound to time, nor race, nor identity, but exploring and expanding history as the lyrical relationship between the individual the world. King Me assesses the pieces of reality fractured by the nightmare of American history in order to reach for a whole, beyond the idea of a fractured reality: a repair—a future. The final poem “Someday I’ll Love Roger Reeves,” the whole is glimpsed, but not grasped. Instead, we get a glimpse, a fragment reveling in the grace of human frailty—a universal condition, which the poet will hold to light:

“And what if this goes on forever?—our ours?

Our drafts and fragments? Our blizzards and our cancers?

Then let us. Then, let us hold each other toward heaven

and forget that we were once made of flesh,

that this is the fall our gods refuse to clean with fire or water.”

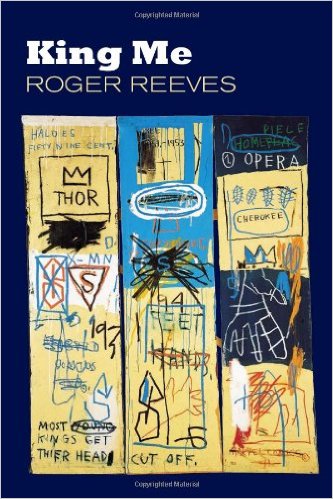

This is a collection that hums with bees, sparrows, thrushes, artists from Keats to Wu Tang to Basquiat to Van Gogh. It is an assertion of voice; a collection of glimpses of history, of our reality, observed and held to the page in their grace. King Me stands as an embrace of the human, the downtrodden, the forgotten and the minute, an ambitious and delicate first collection, which will leave any reader anxious for more from Roger Reeves.

Reviewed by: Evan Goldstein