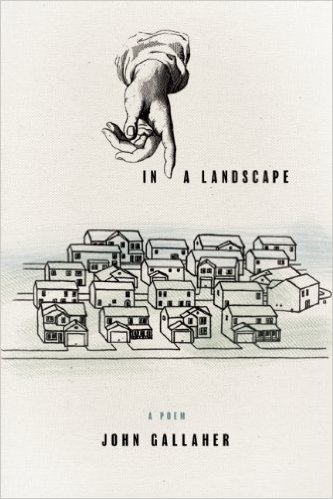

A day after relearning roman numerals up to LXXI with John Gallaher’s seventy-one section poem In A Landscape, I was bed-ridden with a fever and found myself pondering two questions, from a book of many, that arise in its first section: “Are you happy?” and “Is that the beginning of an answer?”

Throughout his autobiographical day-journal, Gallaher asks questions of this caliber that build upon one another and interact, allowing his prose-style poetry to trace an arc as he fumbles and writes for answers. Gallaher’s intimate and undaunted tone draws upon composer, writer, and artist, John Cage’s collection of essays and lectures SILENCE, and Cage’s composition In A Landscape.

The poem explores a type of poetry that dips deeply into prose, but still remains conscience of its position in poetry. Each poem is broken up into three stanzas, or paragraphs, creating an informal beginning, middle, and end for every section. These little stories aim to, or often end up, approaching answers to Gallaher’s accumulating questions. The questions range from almost humorous, such as with, “How many people haven’t you married, that you thought/for a moment—who knows—maybe you would?” to riveting and thought-provoking, as is the case in XLIV in which Gallaher asks: “Is our ability to have confidence in another owing more to others/or to ourselves?”

Gallaher wonders how we get where we are getting, and just where are we getting “in our/‘getting somewhere’ costumes”? In order to help him extrapolate, Gallaher calls in a cast of characters who may get someplace, ranging from his children, Natalie and Eliot, to his wife, Robin, to his ex-neighbor, Matt. Initially dragging you into his life, Gallaher proves that it will be worth it, even helpful, to stick around, as he posits, “ ‘getting out of the way’ is a great way to be helpful.” As an added prose-based bonus, the intimacy bridges the gap of psychic distance between reader and speaker. In fact, I found myself so close to Gallaher at times that it became unnerving and uncomfortable.

Perhaps with hesitation that remains invisible on the page, Gallaher brings in outlying characters, like Todd Carman in XII, “a guy I knew fifteen years ago.” In this poem, Gallaher places us in a frightening reality, while capitalizing on the power of poetic line breaks, for example, in the line: “One night he didn’t come in. He was busy/killing people.” Gallaher remains so matter-of-fact and unflinchingly honest that the reader cannot help but react.

The aforementioned poem, XII, is the only poem with a fourth paragraph, and for good reason as he uses it to soothe our nerves after the story of Todd Carman. While the other seventy have three paragraphs that loosely uphold a sense of beginning, middle, and end, Gallaher makes sure to question his format from early on. The closing lines of III read: “to be there or here without a beginning, or without an ending,/or if perhaps there might be a concept for no middle.”

As much as Gallaher remains aware of the prose elements of his poem, he capitalizes on the poetic elements, for although each section could be said to have three paragraphs, they are truly stanzas and allow for enjambment and end stopping. While his use of enjambment within stanzas is indubitably masterful and poignant, an enjambed line ends a stanza: “of UHF and VHF, how things are always something else//suddenly.” Although a rather shrug-worthy use of enjambment, it is important to note, for it provides further evidence of Gallaher’s awareness of his poetic elements.

After recovering from my fever, I was left wondering if I was being useful, lying in bed all day staying out of people’s way. While Gallaher’s poem approves of my utility, I believe it resonated deeper, ultimately suggesting that life is a catalogue of experiences that matter in one way or another, and Gallaher leaves you wanting to fill the pages of your own life, for better or worse.

Reviewed by: Oliver Diaz